Winning Jeopardy

See the full Jupyter Notebook on GitHub.

Jeopardy is a popular TV show in the US where participants pose questions to the given answers to win money. For this project, let’s imagine we want to compete on Jeopardy and we’re looking for any way to win. We will work with a set of Jeopardy questions to determine some patterns in the questions that could help us wing.

Dataset

The datasest contains 20000 rows and is available here. Each row represents a single question on a single episode of Jeopardy. The columns are

Show Number- the Jeopardy episode numberAir Date- the date the episode airedRound- the round of JeopardyCategory- the category of the questionValue- the number of dollars the correct answer is worthQuestion- the text of the questionAnswer- the text of the answer

When we first load the dataset, we will remove the spaces in these column names. Some of the columns names have leading spaces we will also remove.

Normalizing Text

Before we start our analysis, we need to normalize the text of the Question and Answer columns. In short, we want to put all words in lowercase and remove punctuation so that we don’t consider words such as Don't and don't different words.

To do this, we will write a function that takes a strings, converts to lowercase, removes punctuation, and returns the string.

def normalize_text(string):

lower_string = string.lower()

new_string = re.sub(r'[^\w\s]', '', lower_string)

return(new_string)

We then apply this function to both the Question and Answer Columns, such as

jeopardy['clean_question'] = jeopardy['Question'].apply(normalize_text)

Normalizing Columns

There are a few other columns we need to normalize as well before we start the analysis. The Value column should be numeric, so we will remove the $ sign and convert to an integer. And the AirDate column should be a datetime. These will both be easier to work with after these changes.

Our function to clean the Value column is

def normalize_dollar_values(string):

# we will remove any punctuation to account for any

# data entry issues

new_string = re.sub(r'[^\w\s]', '', string)

# convert to an integer

try:

now_an_int = int(new_string)

except:

now_an_int = 0

return(now_an_int)

And we do the conversion to datetime using pd.to_datetime(SERIES)

Now that we have cleaned and prepared the data, we are ready to begin the analysis.

Answers in Questions

In order to determine whether to study past questions, study general knowledge, or not study at all, it would be helpful to figure out two things:

- How often the answer can be used for a question

- How often questions are repeated

We can answer the first question by seeing how many times words in the answer also occur in the question. We can ansewr the second question by seeing how often complex words (>6 characters) reoccur.

Let’s focus on this first task, which we can accomplish with the following function:

def answer_in_question(row):

# split the clean_answer column around spaces

split_answer = row["clean_answer"].split()

# split the clean_question columns around spaces

split_question = row["clean_question"].split()

match_count = 0

if 'the' in split_answer:

split_answer.remove('the')

if len(split_answer) == 0:

return(0)

for word in split_answer:

if word in split_question:

match_count += 1

return(match_count/len(split_answer))

We apply this to our dataset and find that the answer only makes up about 6% of the question, on average. This means that just listening to the question will not give you a good clue to what the answer is going to be. We will need a different strategy to prepare for Jeopardy.

Recycled Questions

Now let’s answer the second question from above. How often are new questions repeats of older questions? We should not that we are only using about 10% of the full Jeopardy question dataset, but we can still get an idea if this might be fruitful.

To accomplish this, we sort the dataset by the AirDate column, then loop through it to find how often words are repeated. We only consider words with at least 6 characters. This is arbitrary, but should exclude a lot of words that are not specific to the question.

for i, row in jeopardy.iterrows():

split_question = row['clean_question'].split(" ")

split_question = [x for x in split_question if len(x) > 5]

match_count = 0

for word in split_question:

if word in terms_used:

match_count += 1

terms_used.add(word)

if len(split_question) > 0:

match_count /= len(split_question)

question_overlap.append(match_count)

Almost 70% of words have been reclycled from previous questions. While this only includes part of the whole Jeopardy dataset and does not include phrases, it could indicate that it is worth a closer look at the reclycling of questions.

Low Value vs High Value Questions

One potential way to study questions would be to focus only on the high value (>800 pts) questions. This strategy could help us earn more money when on Jeopardy. We can use a chi-squared test to determine which terms correspond to high value questions.

First, we need to break the questions into two categories:

- Low value – any row where

Valueis less than 800 - High value – any row where

Valueis greater than 800.

We can loop through terms_used run a chi-squared test to find the words with the biggest differences in usage between high and low value questions. This function is very slow, so we’ll randomly pick a set of 200 terms from the terms_used list to get an idea of whether or not this is a reasonable approach.

To count the usage of each word, we will use the following function:

def count_usage(word):

low_count = 0

high_count = 0

for i,row in jeopardy.iterrows():

if word in row['clean_question'].split(' '):

if row['high_value'] == 1:

high_count += 1

else:

low_count += 1

return high_count, low_count

Then loop through to calculate the counts using

terms_used_list = list(terms_used)

comparison_terms = [np.random.choice(terms_used_list) for _ in range(200)]

observed_expected = []

for term in comparison_terms:

observed_expected.append(count_usage(term))

And finally, we calculate chi-square and p-values using

high_value_count = jeopardy[jeopardy['high_value'] == 1].shape[0]

low_value_count = jeopardy[jeopardy['high_value'] == 0].shape[0]

chi_squared = []

p_value = []

for pair in observed_expected:

total = pair[0] + pair[1]

total_prop = total / jeopardy.shape[0]

high_value_exp = total_prop * high_value_count

low_value_exp = total_prop * low_value_count

observed = np.array([pair[0], pair[1]])

expected = np.array([high_value_exp, low_value_exp])

chi_sq,p_val = chisquare(observed,expected)

chi_squared.append(chi_sq)

p_value.append(p_val)

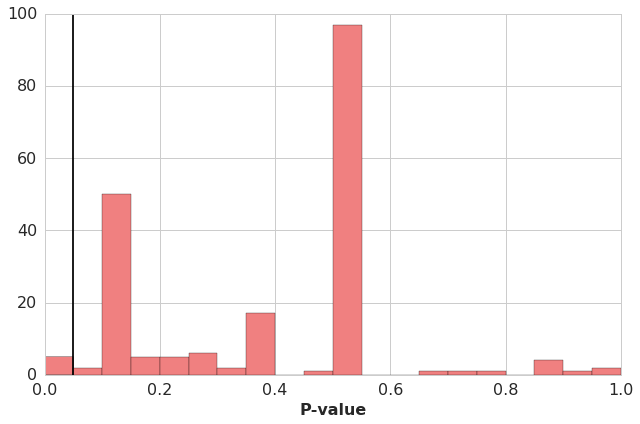

And finally, we can plot the distribution of p-values we just calculated.

We see that only a very small set of words had p-values less than 0.05. And those words all had frequency uses that were very small, leading to a healthy degree of skepticism over the validity. So in summary, there is not an obvious study approach to selecting only terms used for high-value questions.